A funny thing happened while reading Tim Alberta's new book. I thought about becoming a Christian again.

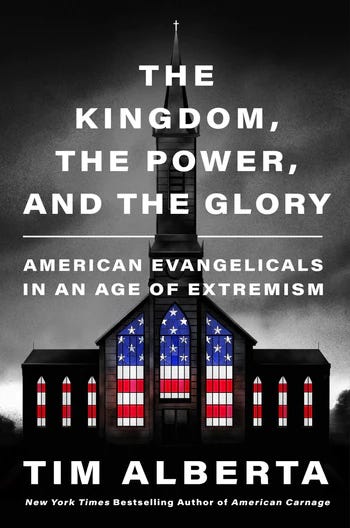

That's maybe not the reaction you would expect to have to "The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory," a deeply reported look at how (mostly white) evangelical Christians have deeply compromised their supposed values to embrace the corrupt and vulgar Donald Trump — not just lending him their votes transactionally, but enthusiastically embracing his slash-and-burn style of authoritarian politics. The corruption, grifting and thirst for power on display is all pretty well-documented by now, but it's still galling (again) to read it all in one place.

Is *this* what Jesus would do?

Alberta doesn't think so.

Jesus "talked mostly about helping the poor, humbling oneself, and having no earthly ambition but to gain eternal life," Alberta writes. "Suffice it to say, the beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount ("Blessed are the meek ... Blessed are the merciful ... Blessed are the peacemakers”) were never conducive to a stump speech."

That’s not very Trumpy.

Alberta brings an interesting set of credentials to this book: Yes, he's a reporter for The Atlantic — part of the hated liberal secular establishment — but he's also the son of a pastor, a devoted Christian himself who (we learn late in the book) is studying at seminary. Alberta is a man who wants the church to be the best version of itself, and that means doing everything it can to glorify God.

What we have here, then, — as I've suggested in recent newsletters — might be the most unapologetically Christian book for a general secular audience that I've read in ages.

How Christian? Put it this way: Alberta devotes several passages throughout the book to the exegesis of Greek words found in the New Testament, the kind of exercise I haven't experienced much since I took Bible classes at a Mennonite college some 30 years ago.

It's also not the kind of thing I'm sure readers of The Atlantic have been exposed to much.

A question I've had about white evangelical Christians in recent years: If they really believe what they profess to believe — that Jesus died on the cross for their sins and was raised to life again, that God is the creator of the universe, that believers will have the ultimate victory in the form of eternal life, that all of this is temporary and fleeting — then why are they acting like this?

One obvious answer is power. "I don’t care if Herschel Walker paid to abort endangered baby eagles. I want control of the Senate," the conservative Dana Loesch said during the notorious 2022 Senate race in Georgia. "How many times have I said four very important words. These four words: Winning. Is. A. Virtue."

The only meaningful virtue for some folks, it seems. But power isn't the only factor here.

* For Chris Winans, the pastor of the church where Alberta's dad spent his career, it's idolatry of sorts. "America," he tells the author about his parishioners. "Too many of them worship America." Lots of Christians see the nation as their primary citizenship and allegiance — as opposed to, say, the Kingdom of God — and act accordingly.

* Fear, both real and false. "These people were scared," Alberta observes after visiting conservative activist Ralph Reed's Faith and Freedom conference. "They were scared, in part, because of economic and cultural instability. But mostly they were scared because people like Reed were trying to scare them; people like Reed needed to scare them. ... The job of a political is to win campaigns. To win campaigns, Reed realized long ago, his most valuable tool was fear."

* Habits of the mind. Most of the folks in the church pews are there for only a few hours every Sunday, if that. But many of them spend the rest of the week listening to far more hours of conservative talk radio or watching Fox News, marinating in apocalyptic anger that paints Democrats and "RINOs" as enemies instead of people deserving of God's love. That shapes the minds and souls of parishioners accordingly.

The result? One of the frustratingly hilarious running themes of the book is how often its subjects — some in positions of leadership or influence in church circles, some not — just flat-out contradict the doctrines and scriptures of their religion. They either don’t know or care about the tenets of their supposed faith. "We’ve turned the other cheek,” Donald Trump Jr. says at one point, “and I understand, sort of, the biblical reference — I understand the mentality — but it’s gotten us nothing. Okay?” That thing Jesus said? No longer operational.

* Or maybe it's just a lack of faith. "You see, the kingdom of God isn't real to most of these people," one pastor tells Alberta. "They can't perceive it."

Why don't white evangelical Christians act like what they believe is true? Maybe they don't really believe.

This doesn’t seem to be good for the church. The number of self-identified Christians in America is shrinking at a steady clip, and while Trumpist politics don’t explain the whole thing, they probably haven’t really helped.

A book like this isn't just supposed to diagnose the problem. It's supposed to offer solutions. It's here that Alberta struggles a bit — though to be fair, nobody has really figured out how to deal with the problem. He points to conservative Christians like Russell Moore and David French who have been cast out of their communities and demonized for their failure to make Donald Trump the lodestar of their faith. He also points to women in the church — a lawyer and a journalist — who have forced institutions like the Southern Baptist Church to account for sexual predation and corruption in their leadership ranks.

So why, for all the terrible things described here, did I find myself tempted to return to the church while reading Alberta's book?

I think it's because Alberta seems passionate about a kind of faith tradition that I was once immersed in. The Mennonites I grew up around were in America because they believed that Jesus had set an example of nonviolence that they were duty-bound to follow, and so had fled their European homelands rather than serve in the armed forces. They really believed in stuff like "love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you."

And so do I, still. I can't explain it. Absent a faith tradition, those words seem almost illogical. Why would anybody pray for their persecutor? I don't have a good answer. All I know is that this is a violent world, and that the idea of loving your enemies is just so profoundly counter-cultural that it has to mean something, right? (Conversely, that's one thing that bothers me about the current crop of Trumpist evangelicals: If you think God is telling you to do something you already want to do ... maybe it's not God talking.)

If that's the case, why don't I actually return to the church?

Well...because I still don't know if what the church says — about the universe, about God, about itself — is actually true.

I don't have faith. It's kind of a problem. So I am not returning to the church, at this point anyway. I've always left the door open.

But I do want the church to be its best self. That doesn't mean evangelicals would adopt my politics, or suddenly become progressive on issues like women's rights, abortion and LGBT issues. It does mean that you'd see more Christians acting like they loved their neighbors, even amidst disagreement. And that’s what Tim Alberta seems to want, too.